Describe common cash flow structures of fixed-income instruments and contrast cash flow contingency provisions that benefit issuers and investors.

Fixed-income instruments are essentially loans that investors make to an entity (like a corporation or government) in exchange for a return on their investment. The cash flow structures of these instruments describe how and when the investor gets paid back.

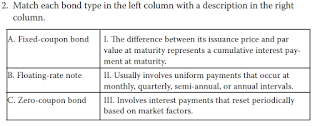

The most common structure is the bullet bond. In this case, the investor lends a certain amount of money, known as the principal, to the entity. The entity agrees to pay a fixed amount of interest on this loan periodically (usually every six months or annually). At the end of the loan term, the entity pays back the principal in full. This is like lending $100 to a friend who agrees to pay you $5 every year and then gives you back your $100 after five years.

Some fixed-income instruments have different structures. For example, in an amortizing loan, the entity pays back a portion of the principal along with the interest periodically. This is like lending $100 to a friend who agrees to pay you back $20 every year for five years. Each $20 payment includes a part of your original $100 and some interest.

Zero-coupon bonds are another type of fixed-income instrument. These are sold at a discount and do not pay any interest during their life. Instead, the investor gets paid the full principal at maturity. This is like buying a $100 bond for $80 and getting paid $100 after five years.

Cash flow contingency provisions are special conditions that can change the cash flow structure of the bond. These provisions can benefit either the issuer or the investor. For example, a call provision allows the issuer to pay back the bond before its maturity date. This benefits the issuer if interest rates fall because they can pay back the bond and issue a new one at a lower interest rate. On the other hand, a put provision allows the investor to sell the bond back to the issuer before its maturity date. This benefits the investor if interest rates rise because they can sell the bond and invest in a new one that pays a higher interest rate.

In summary, the cash flow structure of a fixed-income instrument describes how the investor gets paid back, and cash flow contingency provisions can change this structure to benefit either the issuer or the investor.

Describe how legal, regulatory, and tax considerations affect the issuance and trading of fixed-income securities .

Legal, regulatory, and tax considerations play a significant role in the issuance and trading of fixed-income securities, such as bonds.

1. Legal Considerations: These refer to the laws and regulations that govern the issuance and trading of bonds. For example, the issuer must comply with securities laws, which may require them to disclose certain information about their financial condition and the risks associated with the bond. This is to ensure transparency and protect investors. For instance, if a company wants to issue bonds in the U.S., it must comply with the Securities Act of 1933, which requires the company to register the bonds with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and provide detailed information about the offering.

2. Regulatory Considerations: These are rules set by regulatory bodies that oversee the financial markets. For example, bonds must be issued in accordance with rules set by bodies like the SEC in the U.S. or the Financial Conduct Authority in the U.K. These rules can affect various aspects of the bond, such as its structure, the information that must be disclosed to investors, and how it can be traded.

3. Tax Considerations: These refer to the impact of taxes on the returns from bonds. The interest earned from a bond is usually taxed as ordinary income. However, some bonds offer tax advantages. For example, in the U.S., the interest earned from municipal bonds is often exempt from federal income tax and sometimes from state and local taxes as well. This can make municipal bonds more attractive to investors in high tax brackets.

In summary, legal, regulatory, and tax considerations can affect the structure, pricing, and attractiveness of bonds to investors. Issuers and investors must understand these considerations when issuing or investing in bonds.

Describe A. bullet bond, B. partially amortizing bond, C. fully amortizing bond

A. A bullet bond is a type of bond where the entire principal amount is paid at once upon the bond's maturity. For example, if you buy a bullet bond with a face value of $1000 that matures in 10 years, you will receive the full $1000 only at the end of the 10 years, along with the final interest payment.

B. A partially amortizing bond is a bond that pays back a portion of the principal along with the interest payments during the life of the bond, with the remaining principal paid at maturity. For instance, if you buy a partially amortizing bond with a face value of $1000 that matures in 10 years, you might receive $100 back each year along with the interest payment, and then the remaining $100 at the end of the 10 years.

C. A fully amortizing bond is a bond that pays back the entire principal over the life of the bond along with the interest payments. If you buy a fully amortizing bond with a face value of $1000 that matures in 10 years, you might receive $100 back each year along with the interest payment, so that by the end of the 10 years, you have received the full $1000 back.

Describe difference between . bullet bond and Fully amortizing bond..

A bullet bond and a fully amortizing bond are two types of fixed-income securities that differ in how and when the principal amount is repaid to the investor.

A bullet bond, also known as a standard fixed-coupon bond, is a type of bond where the issuer pays periodic interest payments, also known as coupons, and repays the entire principal amount only at the bond's maturity. For example, if a company issues a 5-year bullet bond with a face value of $1000 and an annual interest rate of 5%, the investor will receive $50 (5% of $1000) every year for five years, and at the end of the fifth year, the investor will receive the final interest payment and the $1000 principal.

On the other hand, a fully amortizing bond is a type of bond where the issuer makes periodic payments that include both interest and a portion of the principal. This means that by the time the bond reaches its maturity date, the entire principal amount has been paid off along with the interest. For example, if a company issues a 5-year fully amortizing bond with a face value of $1000 and an annual interest rate of 5%, the investor will receive payments that include both interest and a portion of the $1000 principal every year for five years. By the end of the fifth year, the investor would have received the total principal amount along with the interest.

In summary, the main difference between a bullet bond and a fully amortizing bond lies in the repayment of the principal amount. In a bullet bond, the principal is repaid in a lump sum at maturity, while in a fully amortizing bond, the principal is repaid in installments over the life of the bond.

Describe common cash flow structures of fixed-income instruments and contrast cash flow contingency provisions that benefit issuers and investors

Fixed-income instruments are essentially loans that investors make to an entity (like a government or corporation), which promises to pay back the loan with interest. The way these payments are structured can vary, but the most common structure is a "bullet bond".

In a bullet bond, the issuer (the one borrowing the money) receives the principal (the initial loan amount) upfront, makes regular interest payments, and then repays the principal at the end of the loan's term. For example, if a company issues a 5-year bullet bond for $300 million with a 3.2% semiannual interest rate, it would receive $300 million upfront, make interest payments of $4.8 million every six months, and then repay the $300 million principal at the end of the 5 years.

However, not all fixed-income instruments follow this structure. Some, like most loans, have principal repayments distributed over the life of the instrument. This means the borrower pays back a portion of the principal along with the interest in each payment. For example, a mortgage is a type of loan where the borrower makes regular payments that include both interest and a portion of the principal.

There are also zero-coupon bonds, which are sold at a discount and do not have any cash flow during their life until the repayment of the principal at maturity. The difference between the discount price and the principal at maturity represents the interest payment.

Cash flow contingency provisions are special features in a bond contract that can benefit either the issuer or the investor. For example, a call provision benefits the issuer. It gives the issuer the right to pay off the bond before its maturity date, which can be beneficial if market interest rates have fallen since the bond was issued. On the other hand, a put provision benefits the investor. It gives the investor the right to sell the bond back to the issuer at a predetermined price, which can be beneficial if market interest rates have risen since the bond was purchased

In conclusion, the cash flow structures of fixed-income instruments can vary, and different structures and provisions can benefit either the issuer or the investor depending on the circumstances.

Describe amortizing debt, fully amortizing, loan, balloon payment, partially amortizing bond

Amortizing debt is a type of loan where the borrower makes regular payments over a set period of time. Each payment includes both principal and interest. Over time, the principal portion of each payment increases and the interest portion decreases, so by the end of the loan term, the entire debt is paid off. For example, if you take out a car loan for $20,000 with a five-year term, you would make monthly payments that include both principal and interest until the entire $20,000 is paid off at the end of five years.

A fully amortizing loan is a specific type of amortizing debt where the entire principal amount is paid off over the term of the loan. This means that at the end of the loan term, there is no remaining balance or "balloon payment" due. For example, a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is a fully amortizing loan. If you borrow $200,000 to buy a house and make all of your monthly payments on time, you will have paid off the entire $200,000 after 30 years.

A balloon payment is a large, lump-sum payment that is due at the end of a loan term. This typically occurs in a partially amortizing loan, where the borrower makes smaller regular payments, but the full amount of the principal is not paid off over the term of the loan. Instead, the remaining balance is due as a balloon payment at the end of the term. For example, you might take out a five-year loan for $100,000, but only $60,000 is amortized over those five years. At the end of the five years, you would owe a balloon payment of $40,000.

A partially amortizing bond is a type of bond where the issuer makes regular interest payments to the bondholder, but only a portion of the principal is repaid over the term of the bond. The remaining principal is paid as a lump sum at the end of the bond's term. For example, a company might issue a 10-year bond with a face value of $1,000, but only $600 is amortized over the 10 years. At the end of the 10 years, the company would owe a balloon payment of $400 to the bondholder.

Describe sinking funds, waterfall structures

Sinking funds and waterfall structures are financial mechanisms used in the repayment of debt.

A sinking fund is a way for companies to pay off part of their bond issue before it reaches maturity. It is a fund into which a company sets aside money over time, specifically for the purpose of retiring its debt. For example, if a company issues a $20 million bond due in 10 years, it might create a sinking fund to repay that bond. Instead of making the investors wait for 10 years to be paid, the company might repay $2 million each year. This reduces risk for investors, as it lessens the chance that the company will not have sufficient funds to pay the bond when it matures.

A waterfall structure, on the other hand, is a method of distributing the cash flows from a bond issue to different classes of investors, also known as tranches. In a waterfall structure, the cash flows are distributed sequentially, starting with the most senior tranche, then moving to the next senior tranche once the previous one is fully paid off. For example, consider a company that issues three tranches of bonds: A, B, and C. Tranche A is the most senior, followed by B and C. In a waterfall structure, all principal and interest payments go to Tranche A investors until their bonds are fully paid off. Only then do payments start going to Tranche B investors, and so on. This structure prioritizes the repayment of the most senior tranches, reducing risk for those investors.

Describe market reference rate (MRR), credit spread, floating-rate loan assets, floating-rate notes (FRN)

Market Reference Rate (MRR): The MRR is a benchmark interest rate that floating-rate notes (FRNs) or loans are tied to. It is usually a short-term money market rate. For example, the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) is a common MRR. It is the rate at which banks lend to each other in the London interbank market.

Credit Spread: The credit spread is the difference between the yield of a corporate bond and the yield of a government bond with the same maturity. It reflects the additional risk of the corporate bond compared to the risk-free government bond. For example, if a corporate bond yields 6% and a government bond yields 4%, the credit spread is 2%.

Floating-Rate Loan Assets: These are loans where the interest rate changes periodically based on changes in a reference interest rate. For example, a bank might issue a mortgage with an interest rate that adjusts every year based on changes in the U.S. Prime Rate.

Floating-Rate Notes (FRN): An FRN is a bond that has a variable coupon, equal to a money market reference rate, like LIBOR or federal funds rate, plus a quoted spread. The spread is a rate that remains constant. For instance, if the LIBOR rate is 3% and the quoted spread is 2%, then the interest rate for the FRN would be 5%.

For example, Antelas AG, a German technology company, issued a four-year FRN with a principal amount of EUR250 million. The interest rate is set as MRR plus 250 basis points per annum, which means the interest rate will adjust based on the MRR, with an additional 2.5% added on top. The MRR is reset quarterly, and interest is paid quarterly

Reference:

Describe payment-in-kind (PIK), green bonds, leveraged loans, credit-linked notes, step-up bonds

Payment-in-kind (PIK) is a type of financing where the interest or principal is not paid in cash but rather by increasing the principal amount of the loan or bond. For example, if a company has a PIK loan of $100 with an annual interest rate of 5%, instead of paying $5 in cash at the end of the year, the loan principal would increase to $105. This is often used by companies with high debt levels or cash flow problems, as it allows them to defer cash payments

Green bonds are a type of fixed-income instrument used to finance projects with environmental benefits. For example, a company might issue a green bond to raise money for a new renewable energy project. Investors who buy these bonds are essentially lending money to the issuer for this green project, and in return, they receive periodic interest payments and the return of the principal amount at the end of the bond's term

Leveraged loans are loans provided to companies or individuals that already have considerable amounts of debt. Borrowers might use leveraged loans to finance mergers and acquisitions, recapitalizations, or refinance existing debt. For example, if a company with a significant amount of debt wants to acquire another company, it might take out a leveraged loan to finance the acquisition

Credit-linked notes are a type of security that has its cash flows linked to the credit performance of a reference entity. For instance, if a company issues a credit-linked note and the reference entity defaults on its debt, the investors in the note could lose some or all of their investment. This type of note is often used as a way for investors to gain exposure to specific credit risks

Step-up bonds are bonds that have a coupon rate that increases over time at predetermined intervals. For example, a step-up bond might have a coupon rate of 2% for the first two years, 3% for the next two years, and 4% for the final two years. This type of bond can be attractive to investors who believe that interest rates will rise in the future .

Describe Index-linked , inflation-linked bonds, Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities(TIPS), capital-indexed bond, interest-indexed bonds.

Index-linked or inflation-linked bonds are a type of bond where the principal amount or the interest payments are adjusted according to the rate of inflation. This means that the value of the bond increases with inflation, protecting the investor's purchasing power.

For example, let's say you buy a $1,000 inflation-linked bond with a 2% annual interest rate. If inflation is 3% over the year, the principal value of your bond would increase to $1,030. Your interest payment for the year would then be 2% of $1,030, or $20.60, instead of $20. This way, your investment keeps pace with inflation.

A well-known example of inflation-linked bonds are Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) issued by the U.S. government. The principal of a TIPS increases with inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index. When a TIPS matures, you are paid the adjusted principal or original principal, whichever is greater.

Capital-indexed bonds are similar to inflation-linked bonds, but the principal is adjusted according to a specific index, such as a stock market index. This means the value of the bond can go up or down depending on the performance of the index.

Interest-indexed bonds, on the other hand, have a fixed principal value, but the interest payments are adjusted according to a specific index. This could be an inflation index, a stock market index, or an interest rate index. For example, if the index goes up by 2%, the interest payment would increase by 2%.

These types of bonds can be a good investment if you expect inflation or the specific index to rise. However, they can also be riskier than traditional bonds because the value can go down if the index falls.

Describe Zero-Coupon Structures, Deferred Coupon Structures, with example

Zero-Coupon Structures are a type of bond that does not make any interest payments until the bond matures. Instead, they are sold at a discount to their face value. For example, you might buy a zero-coupon bond for $900 that will be worth $1,000 in a year's time. The $100 difference between the purchase price and the face value is the interest you earn. These types of bonds are often used by governments and are particularly common when interest rates are very low or even negative.

Deferred Coupon Structures, on the other hand, are bonds that do not pay any interest for a certain period after they are issued. After this period, they start paying a higher rate of interest. For instance, a company might issue a deferred coupon bond that pays no interest for the first three years, but then pays a higher rate of interest for the remaining years until it matures. This can be useful for companies that are undertaking large projects that will not generate income until they are completed.

Both of these types of bonds have different risk and return profiles and can be useful in different situations. For example, zero-coupon bonds can be useful for investors who do not need regular income and are looking for a guaranteed return at a specific point in the future. Deferred coupon bonds can be useful for companies that need to raise money but do not have the cash flow to make regular interest payments immediately.